Flaunt Weeekly

The Miseducation of Mario Vargas Llosa

A most contemporary sequence, The Name of the Tribeexplains why the Peruvian creator rejected the left and embraced the thinking of Friedrich Hayek and his ilk.

In a 1949 paper published in the Bulletin of the American Association of College Professorsthe liberal logician Sidney Hook described a definite species of mid-century intellectual who, having long regarded to the Soviet Union as a monumental experiment in human emancipation, became impelled, for one reason or but every other, to doubt and in the ruin abandon that conviction. The flight of the man vacationers, including the likes of W.H. Auden, Edmund Wilson, André Gide, and Bertrand Russell, became born no longer out of mere disappointment or embarrassment nonetheless, Hook insisted, one thing deeper and map more troubling: a roughly non secular disenchantment that upset the foundations of a shared political identity. What resulted from this “decay of faith,” as Hook termed it, became a “literature of political disillusionment,” a subgenre in the confessional vogue whereby that failure became build on fats present, examined, and in the ruin transformed into maturity. The predominant language whereby this maturity expressed itself became liberalism.

As a rule, after we hear about political disillusionment in the polling and punditry of our second, it is disillusionment with liberalism itself. In opposition to every person foes, from autocratic putsches at home and in a international nation to leftward agitation on the labor and electoral fronts, self-described centrists, realists, and liberals get themselves on their guard, in the sad situation of attending to defend an curiously crumbling location quo.

Though Hook, who additionally began his occupation as a Marxist, focused primarily on the implosion of the Soviet superstar in the eyes of left-leaning Western intellectuals, this trajectory from left to center (and previous) as a route of of realization is a wanted instrument in ideological self-narration. From Immanuel Kant’s definition of enlightenment as “man’s emancipation from self-imposed immaturity” in the categories of political and non secular authoritarianism to Irving Kristol’s description of a neoconservative as a liberal (though right here he supposed anybody left of the American center) who has been “mugged by actuality,” the appropriate of necessary of mainstream political idea has been the slack plod from imposed demands and Icarian fantasies correct into a utopia of grown-ups, making choices no longer on the foundation of bought idea, or even of suggestions, nonetheless in accordance with the transparently “rational.”

What carries us on the manner to this besotted realm? For a lot of Enlightenment and 19th-century liberal thinkers, it became Christianity—especially in its Protestant, bourgeois kinds—that provided a roughly ladder to political maturity that would additionally, eventually, be kicked away. Nonetheless with the behind erosion of that faith, as effectively as a protracted-established skepticism about the inevitability of growth, would possibly also a literature of political disillusionment support that role? And what can we fabricate of this different, which brings us to maturity no longer by hope nonetheless by disappointment? Is there, in the ruin, a different between the 2?

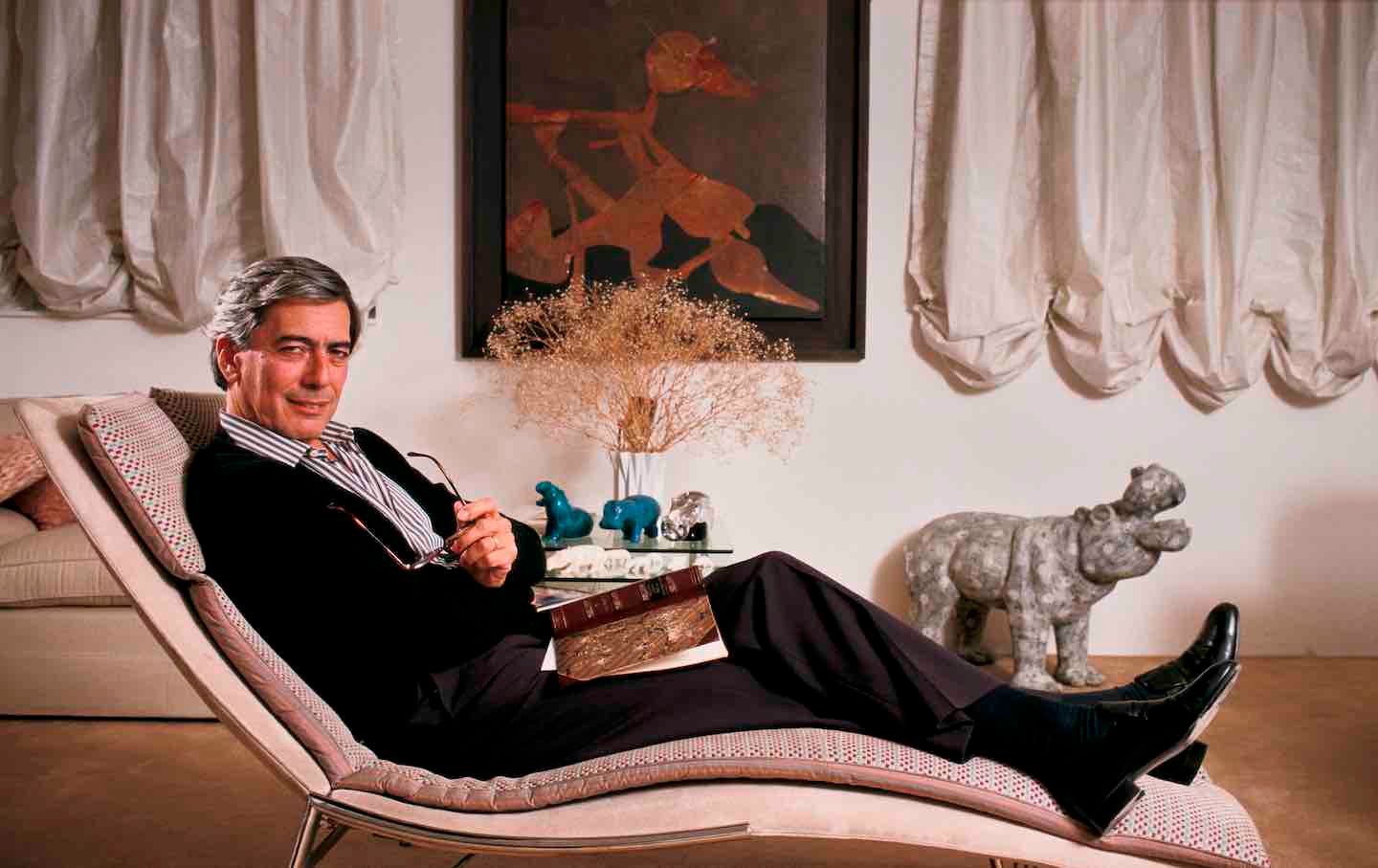

In the route of his a protracted time-long occupation, the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa has added essential to this literature. His early novels, equivalent to 1966’s The Inexperienced Home and 1969’s Conversations in the Cathedralexplored the sources of decay that result in each and every institutional corruption and private despair. And in his essays, articles, and speeches, Vargas Llosa has long been among essentially the most noteworthy literary defenders of the Western liberal expose. Now the octogenarian Nobel laureate and newly elected member of the Academie Française (the first non-Francophone member in its history) gives a summation and justification of that effort in The Name of the Tribea look of seven key thinkers who helped him shed his youthful socialist idealism and oriented his soul in opposition to the sunshine of republican democracy and market capitalism. That record of luminaries entails the Scottish economist and “father of liberalism” Adam Smith; the Spanish existentialist José Ortega y Gasset; the Austrian American economist Friedrich Hayek; the Austrian British logician of science Karl Popper; the French logician Raymond Aron; the Russian British political theorist Isaiah Berlin; and the French public intellectual Jean-François Revel.

In the e book’s introduction, Vargas Llosa gives long-established reflections on his private political ride and his disenchantment with leftism, as effectively as more pointed feedback on the role of the express as a protector of individual liberty and administrator of education, each and every public and private. (Training, for Vargas Llosa, is a wanted info level in the reliability of opponents as an engine for quality and growth; he’s in particular taking into account voucher methods. He attributes these suggestions to the Chicago economist Milton Friedman, one of many godfathers of neoliberalism.)

The account that Vargas Llosa tells of his political formation is that of a younger man, born correct into a center-class nonetheless effectively-connected family, and who spent time in Cuba in the 1960s, handiest to search out himself an increasing number of alienated by what he took to be Castro’s autocratic tendencies. The breaking level became what’s now acknowledged as the Padilla Affair, whereby the poet and public intellectual Herberto Padilla—an preliminary supporter of Castro’s executive, who turned its an increasing number of strident critic—became arrested in 1971 on the grounds of creating counterrevolutionary statements, as effectively as accusations that he became acting in the make utilize of the CIA (an “absurd accusation,” in line with Vargas Llosa).

Padilla’s link to American intelligence remains in dispute (a letter to The Guardian in line with the paper’s elegant obituary of him in 2000 suggests conflicting proof), nonetheless, up to now as I will squawk, that became neither the associated price that received him arrested nor what introduced about Vargas Llosa, alongside with different public intellectuals in the West, to interrupt with Cuba. A self-evidently coerced public confession by Padilla adopted his arrest, which became a long way too paying homage to the Stalinist present trials that an earlier skills of intellectuals had condemned, and this led Vargas Llosa—alongside Susan Sontag, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others—to publish an launch letter denouncing Castro’s obvious authoritarian turn. Padilla himself lived in a traumatic détente with the regime for but every other decade prior to transferring to the USA and teaching at Princeton, nonetheless for Vargas Llosa, no longer handiest the Cuban finishing up nonetheless leftist politics as a total had been now irredeemably substandard.

It is in this context that Vargas Llosa’s precept of quite a lot of in The Name of the Tribe turns into clearer: The thinkers he examines are exclusively European and male, an indication no longer so necessary of Eurocentrism and sexism (a minimal of no longer instantly) as of the roughly thinking that he finds most compelling. When drawing up a checklist of thinkers who took liberalism significantly as per chance the supreme closing political probability in the twentieth century, other than the likes of Hannah Arendt and Judith Shklar would possibly be a damnable oversight. Nonetheless strict theorizing is no longer any longer precisely the terrain Vargas Llosa wants to duvet right here. As an different, as his occupation has shown (as well to his literary and journalistic work, Vargas Llosa has additionally been a highly viewed political figure, even running in Peru’s 1990 presidential election at the head of the heart-valid Frente Démocratico), he is most alive at the boundary of idea and action. He is therefore drawn to the thinkers who, both by intervention or affect, crossed that line and turned unofficial spokesmen for world occasions. And though Vargas Llosa is at disaster to painting liberalism as a “monumental tent” (his phrase), definite subject issues emerge to offer a rough-and-willing outline of what, for him, constitutes liberal thinking.

Liberalism’s key advantage, Vargas Llosa insists, is the primacy it grants to the individual over the collective. The title of the amount, The Name of the Tribecomes from Popper, who is doubtless to be most noteworthy for The Originate Society and Its Enemieshis fundamental-ancient legend of the intellectual origins of authoritarianism. This look, which assaults Plato, Hegel, and Marx for his or her “historicism” (Popper’s curiously misapplied time frame for social thought aimed at the prediction of future occasions), is composed taken significantly by many liberals, no topic a mammoth consensus that Popper’s thesis is in line with a profound misreading of every and every political and intellectual history. Vargas Llosa cites him, alongside with Hayek and Berlin, as having had essentially the most tantalizing affect on his private political vogue, in particular in coming to realize the role of liberal society as the protector of the individual against the ever-hide risks of primitivism and irrationality, the anti-civilizational “call of the tribe.”

For Vargas Llosa, as for the total thinkers he explores, the history of the twentieth century is the combat of the liberal West against various manifestations of that resolution, which, in in vogue societies, takes the set up of the mass or crowd. Citing Ortega’s Insurrection of the Masseswhereby the emergence of the crew in in vogue cases is analyzed and warned against, Vargas Llosa writes: “The ‘mass’…is a neighborhood of those that non-public turn into deindividualized, who private stopped being freethinking human entities and private dissolved into an amalgam that thinks and acts for them, more thru conditioned reflexes—feelings, instincts, passions—than thru reason.” Crucially right here, the liberal ideal is no longer any longer a impartial to be finished nonetheless a unbiased express to be fetch. It is, in this telling, the natural set up of human existence, as against the imposed structures of any other roughly social group. Such naturalism is no longer any longer merely an inclination nonetheless a predominant tenet of Vargas Llosa’s liberalism, and it accounts no longer valid for the vehemence with which he assaults the idea that he believes threatens it (above all, the leftist positions he claims as soon as to private held), nonetheless additionally for the manner in which he defends what’s now the mainstream—no longer to command hegemonic—social expose.

Beginning with Adam Smith—who, we are told, “emphasizes that express interventionism is an infallible recipe for economic failure due to it stifles free opponents”—Vargas Llosa insists on the link between unencumbered economic process and human freedom on the total, a conviction that determines his review of every and every of his key thinkers. In all, Hayek looks to catch out as essentially the most tantalizing among them: “No one,” Vargas Llosa writes, “has outlined greater than Hayek the benefits to society, in all areas, of this methodology of exchanges that no-one invented, that became born and perfected by probability, above all by that ancient accident called liberty.” If fascism (or connected kinds of despotism), in Vargas Llosa’s estimation, is a menace on the grounds of its irrationality, then leftism, from democratic socialism to Soviet communism, remains a increased menace composed for its overestimation of human reason. Given liberalism’s defeat of its rival methods (this, useless to reveal, is the ancient legend we’re working with right here, no topic the wanted Soviet role in destroying the Third Reich and the next absorption of used Nazis into the liberal West, from Kurt Waldheim to Klaus Barbie), the enemy to be resisted is the specter of planning.

The rejection of planning, which Vargas Llosa attributes to each and every Hayek and Popper, is an advanced belief to preserve philosophically in your suggestions. After all, human affairs attain no longer merely unfold. Other folks reply to stimuli and instruction, alternatively implicit, and it is governments and social institutions, among other issues, that set up the stipulations of the classes we study. The critique of planning, then, looks no longer to be the different of freedom over resolution, nonetheless somewhat the prefer for definite kinds of choices over others.

Nonetheless I mediate this is no longer any longer a quiz of argumentative slippage, necessary less of hypocrisy on Vargas Llosa’s phase. In keeping with his sequence of thinkers, his curiosity is no longer any longer in dissecting the arguments for liberalism nonetheless merely in defending them, by whatever manner present efficacious. The Name of the Tribe is as necessary a manifesto and a homage because it’s a look.

Vargas Llosa’s rejection of the left, then, is basically in line with the gruesome actions committed by some leftists, which he takes to be indicative of the rot at the coronary heart of your total endeavor. When he learns of Castro’s detention centers, he sees them as proof of the regime’s elementary nature. By distinction, the regimes of every and every Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan are praised for introducing a sleek dynamism into British and American existence—and as for his or her funding of death squads from Ulster to El Salvador, the flourishing of non-public prisons, or the roughly fixed express of crisis we private lived below since this neoliberal revolution, these are, to the extent that Vargas Llosa addresses them at all, so many broken eggs on the earth-ancient omelet. In less triumphant moments, the e book’s message looks to be that when a liberal executive commits crimes and human rights abuses, it is merely failing to realize or are residing up to its private beliefs.

Nonetheless the contents of liberalism itself are subject to in the same map shifting sands, even opposite tendencies. When Ortega fails to acknowledge the prevalence of free-market capitalism to central planning, Vargas Llosa deems his liberalism “partial,” whereas Hayek’s liberalism consists precisely in his transcending the merely economic. And when Hayek praises the murderous, repressive regime of Augusto Pinochet, this is merely an instance of one of his “convictions [that] are sophisticated for an professional democrat to portion.” No more discussion is given to the topic. Per chance Vargas Llosa is remembering who the valid enemy is: When Pinochet became arrested for crimes against humanity in 1999, Vargas Llosa penned an op-ed for The Unusual York Times asking why, if the enviornment became willing to condemn the valid-flit dictator, it became no longer additionally willing to condemn the left-flit dictators of the enviornment, chief among them Castro.

Vargas Llosa retains necessary of his strength as a prose stylist, and there are moments when The Name of the Tribe provokes a exact thrill of discovery—a plan that, for valid or ill, it became these men whose suggestions private driven the history of the closing half-century. On the opposite hand, there are valid as many moments when these accounts of intellectual adventure and individual liberty originate to sag, when the insistence that no design or ideal as a change of free-market capitalism and liberal democracy would possibly also additionally be definite that the stipulations for individual and social flourishing turns into virtually a mantra, an utterance unanswerable no longer due to it is flawless, nonetheless due to it doesn’t seem made with dialogue in suggestions.

What does this sort of hagiographic manner offer to anybody who is no longer any longer already a believer? This quiz returns us to what we can study from the literature of disillusionment. Why, when liberalism is merely the natural and rational situation to preserve, does it require this sort of defense? Vargas Llosa permits us a spy in the reduction of the curtain in his discussion of the argumentative vogue of the outwardly modest Isaiah Berlin: “Handsome play,” he writes, “is handiest a plan that, cherish every story ways, has valid one feature: to fabricate the yell material more persuasive. A account that looks no longer to be suggested by anybody in explicit, that purports to be increasing itself, by itself, for the time being of learning, can often be more plausible and fascinating for the reader.”

So why disillusionment? It’s a story mode with glaring non secular connotations; it’s a account about the revelation of the valid faith, the smashing of unfounded idols and the embody of pure faith, at which level “faith,” as such, turns into the enemy, or a minimal of a hazard to be wary of. This identical constructing performed out in colonial encounters—colonists described natives first as having no faith and then, as soon as European Christianity gave manner to secular humanism, as being slaves to it. So it is completely consistent to hide Marxism or leftist politics on the total, as Vargas Llosa does (drawing especially on Popper and Raymond Aron), as old-customary, tribal, non secular. “Religion,” in this customized, is what folks attain.

It is that this ancient double play that illuminates the valid strength of the story of disillusionment. It aids in the creation no longer of two sides of an argument, nonetheless of a natural (that’s, a non- or even subhuman) phenomenon and a unbiased observer. Such an observer would possibly also private a commitment to “flexibility,” as Varga Llosa insists that every and every liberals—whether individual thinkers or governments—must, nonetheless this sort of duality on the opposite hand is reckoning on a in moderation guarded wall between the wildness available and the reason in right here. It is the complexity of a world of actions and members of the family, choices and penalties, congealed correct into a world of decided potentialities that will dwell hidden unless you merely, though per chance painfully, grow up. When the ask is made so insistently, one begins to shock what measures would possibly also very effectively be justified in dragging the reluctant into the sunshine.

I in fact private to admit that by the ruin of The Name of the TribeI felt a roughly malaise, having read the litany of liberal advantage in so many iterations. Why, the quiz nagged, in its fourth (or, arguably, eighth) decade of virtually unchallenged international hegemony, attain the representatives of Western liberalism in fact feel the must defend it against threats that had been for goodbye neutralized? After which it took place to me that this one year marks the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup d’état, the death of Salvador Allende, and the starting of a a protracted time-long tyranny supported and praised by, among others, Hayek, Friedman, and the US executive. Allende, because it occurs, is one democratically elected socialist for whom Vargas Llosa, if this e book is any indication, retains some sympathy, if handiest in retrospect. Per chance, he looks to imply, the transition to a more fully liberal economy would possibly also had been finished more easily, less forcefully. Serene, the Chicago Boys took over, the left became destroyed, and it is in the nature of news to be retold, of rituals to be performed, of victories to be commemorated.