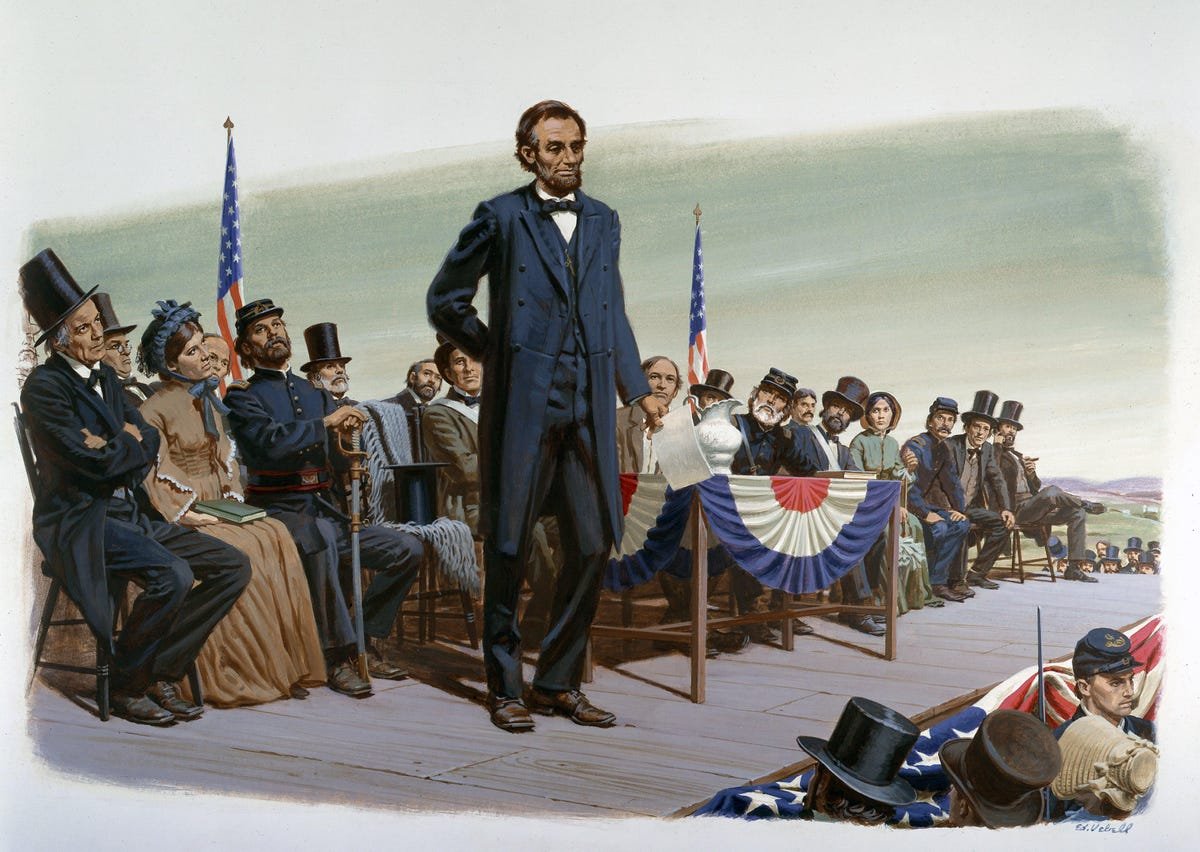

(Illustration by Ed Vebell/Getty Images)

Abraham Lincoln richly deserves his own day instead of getting mashed into the employer-convenient “President’s Day.”

Doubtless he deserves his own holiday as a martyr fighting to preserve the union, promoting economic equality and laying the groundwork for the slavery-ending 13th, 14th and 15th amendments.

Yet there’s a lesser-known reason why Lincoln deserves a special day of remembrance: Building Infrastructure. I know that’s not as elegant sounding as his Gettysburg Address or his inaugural speeches, but he did more to build this country’s public works than any other president (until recently) up until FDR’s New Deal.

In researching my book “Lincolnomics,” I discovered how Lincoln became our first great champion of infrastructure — surprisingly during the height of the Civil War.

Lincoln had an early head start on promoting public works. When Lincoln began his political career in the 1830s, he championed canals, which, combined with existing ports and rivers, were the interstates of that time. Then he supported land-grant railroads, which eventually created an epic transcontinental transportation network. The Illinois Central, for example, was the longest railroad in the world at the time of his inauguration in 1861. He even dabbled in urban planning, drafting a plan for “Huron,” a new town platted on the Illinois River that was situated on a junction with a canal that he advocated, but was never built.

Amidst the horrors of the Civil War, Lincoln doubled down on infrastructure. He supported the Morrill land-grant college act and the Pacific Railway Actswhich seeded the transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869.

Of course, there’s no denying that giving away land that belonged to Native Americans and enabling mostly white homesteaders to populate the West did grievous harm to indigenous tribes. We still need to reconcile that genocidal purge.

Yet the basic necessity to consistently invest in all forms of infrastructure should be part of our social compact. Last year’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Protection Act does much to bolster infrastructure and address climate change, but we need an ongoing capital fund that’s constantly being replenished. Modeling it after the sovereign investment funds of Norway and Singapore would be a start.

Thanks to President Biden and Congressional supporters who were channeling Lincoln, FDR and Eisenhower. Still, we’re not even close to what we need to do. Creating a robust social infrastructure fund is also essential.

Social Infrastructure Needs A Major Upgrade

While repairing and upgrading bridges, roads and water systems across the country was long overdue, social infrastructure is in dire need of continuous funding.

We’re currently facing a shortage of teachers, nurses, paramedics and police. We sorely need more basic behavioral and community medicine and caregivers. We desperately need affordable housing, college, trade schools and have to replace millions of tradespeople and first responders who are retiring.

If the COVID crisis taught us anything, it was that our public health infrastructure was inadequate, especially in low-income, rural and communities of color. Small towns from Appalachia to the Pacific are struggling to attract and retain doctors and nurses. Public hospitals are bursting at the seams. Too many Americans lack decent health insurance or access to low-cost community medical care.

There’s a pernicious inequity gnawing at our collective health and well being. Research shows that communities of color had much worse outcomes during the pandemic than predominantly white areas: Health inequality has long plagued underserved communities. That persistent issue needs to be addressed.

Lincoln continues to be a durable inspiration for building a better America and getting beyond the “mystic chords of memory” and fulfilling his pledge to make America “the last best hope on earth.” It’s not surprising that Lincoln was one of the first presidents to invoke the phrase “climbing the economic ladder.”

Today with inflation, interest rates and economic disparities between the middle class and top 1% creating a deep chasm, we need to repair and replace the rungs on the financial ladder of the American dream, Lincoln’s original core mission. It will take more than “the better angels of our nature” to do that. A comprehensive, permanent infrastructure program is one way to address this undeniable need.